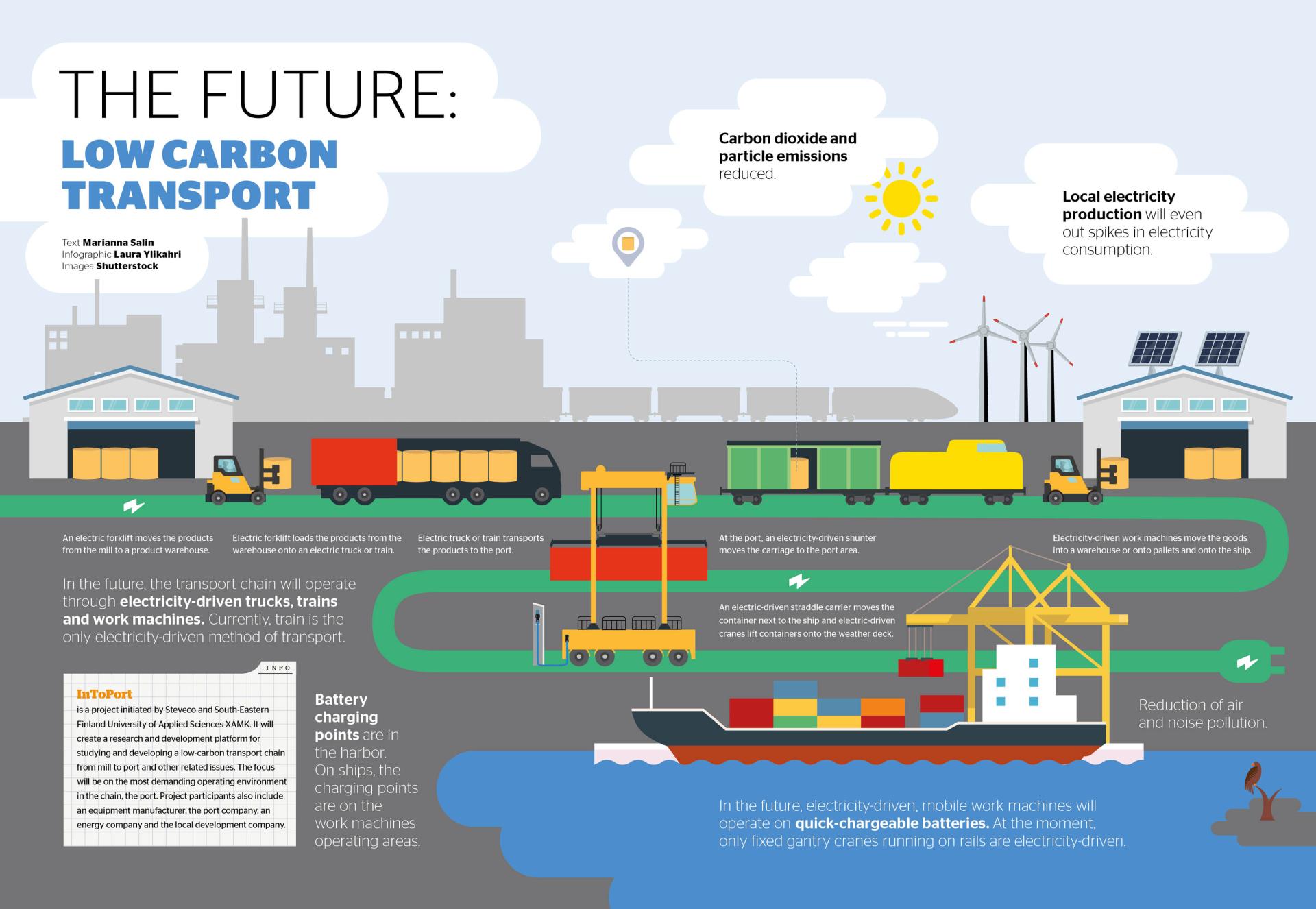

Low-carbon transport chain from mill to port

In future, electric trucks and electricity-driven work machines will cut the CO2 emissions in product transport chains. How much? At what price? When? These are some of the questions to which Steveco intends to find answers in collaboration with research partners.

The trend is clear. Customers are more and more interested in how products have been manufactured and where their raw materials come from. When carbon dioxide emissions come under comparison, the transport chain also figures. “We believe that a low-carbon transport chain will increase in importance in future, and we want to contribute to its research and development,” says Heikki Jääskeläinen, Senior Vice President, Roro Operations, Steveco.

In Steveco’s vision, an electric forklift moves the products from the mill to a product warehouse, and later on, loads them on an electric truck or train that transports them to the port. At the port, electricity-driven workmachines move the goods into a warehouse or on pallets and on to the ship.

Because no readily available solutions exist, Steveco is starting a cross-disciplinary research project called InToPort with South-Eastern Finland University of Applied Sciences XAMK, plus other partners. “The demanding operating environment at a port is a good basis for R&D work whose results also other actors in the transport chain may take advantage of.”

A more powerful electric forklift

trukkiPart of port equipment is already electrically driven. These include the fixed gantry cranes running on rails. At the Hietanen port in Kotka, Southeast Finland, all machines run on wheels, because they load roro ships, to which the goods are rolled on and from which they are rolled off. Forklifts move pallets and rolls in the warehouse and in the holds of the ship. Terminal tractors move pallets on shunting trailers, and mobile cranes lift containers on to the weather deck. All this equipment is powered by diesel engines. Does an alternative to the internal combustion engine even exist?

Laura Hasko, Development and Quality Manager, Steveco, admits that electric forklifts have had a bad reputation at ports, and for a good reason. They are fine in a wholesaler’s warehouse where one-tonne lift capacity is more than enough, but at the Hietanen port, the smallest load is a couple of tonnes, and the largest as much as six tonnes. Some of the port’s diesel forklifts lift up to 28 tonnes.

Feedback from the port is now changing, though. Hietanen received an electric forklift for testing last year. It can lift eight tonnes. Jouni Hinkkanen, stevedore, says the machine works as well as diesel forklifts with the same weight. “It is a good machine to drive. Quieter and smoother. The battery makes it a bit bigger,” he sums up.

Quick charging coming soon

For a lay person, it is easy to place his bets on the electric forklift when it begins its nimble dance right next to a roaring diesel forklift. After six hours, however, his opinion might change. The electric forklift is getting exhausted, goes to charging, and comes back to work only the next morning. “With a diesel truck, a full fuel tank allows driving two shifts, that is, 16 hours,” says Mr Jääskeläinen. He says an electric truck will not be a viable option until it manages one working day one way or another. Present battery development does not encourage waiting for the introduction of a battery sufficient for a whole workday. Mr Jääskeläinen considers a more probable solution to be quick charging during breaks. Having closely followed the development of straddle carriers, he knows that five-minute charging once every hour is being tested, but there is still a lot to be developed. “We want to offer equipment manufacturers a testing environment where the machines are compelled to do the work they are intended for,” Mr Jääskeläinen says. The research project gives an opportunity to analyse operating experiences in more details than at present.

Peak power under the magnifying glass

If quick-chargeable work equipment were the only requirement for a low-carbon transport chain, the people at Steveco would hardly be starting a research project.

“We also have to be clear on how charging fits our workflow, where the charging stations should be, and whether the ships have a role in charging,” Ms Hasko lists the issues. The greatest challenge, however, is the power required by charging. What happens when the stevedores have their break and leave their machines to be charged? The power peak is hardly covered by turning off the lights in the office – or even in the whole city. “It would also be good to be able to charge the batteries of the road vehicles during unloading,” Ms Hasko adds another point.

At present, it is impossible to assess the charging power requirement as no electrically driven work equipment exists yet, but Ms Hasko is hopeful that the research project will provide answers. “At the same time, we want to study possibilities for generating electricity.” This is one reason why the local energy company is one of the research partners in the project.

Self-generated solar power

One solution for power generation can be seen through the window of the Hietanen port terminal. The spring sunshine from a clear blue sky lights up the roofs of the warehouse buildings. Roofs that together make up 130,000 square metres.

“If we installed solar panels on the roofs, work could continue at least when the sun is shining,” Ms Hasko chuckles. Even though Kotka is considered one of Finland’s sunniest cities, she admits that besides solar power generation, power storage and other ways of generation need to be studied.

Mr Jääskeläinen and Ms Hasko expect the project to offer estimations of purchase and energy costs, as well as CO2 emission reductions that a low-carbon transport chain could create. “The purchase cost of equipment will probably rise a little in the beginning, but operating costs will go down,” Mr Jääskeläinen thinks.

Down with all emissions

It is clear already that a shift to electrically driven work equipment would reduce both carbon dioxide and particle emissions. Steveco has paid attention to this for years. For example, some of the port’s forklifts, staddlers and terminal tractors have catalysers that reduce nitrogen oxides with a urea-water solution. “In the research project, we intend to compare the operation and emissions of regular diesel forklifts, urea forklifts and electric forklifts,” Mr Jääskeläinen says.

When diesel forklifts operate in ships’ cargo holds, about five metres high, their exhaust fumes are sucked out by the ship’s efficient ventilation system. When the project progresses, it is expected to show how much the reduction of exhaust fumes will reduce the need for ventilation on board the ships and thus the ships’ power generation requirements. “We will also study whether the electricity generated by the ship could be used for charging,” Mr Jääskeläinen reveals.

As far as the working environment goes, the deployment of quiet and emission-free work equipment seems nothing but a positive development, but not even that is taken for granted in the Steveco project. Ms Hasko points out that a silently moving electric forklift is difficult to notice. “In the project, we intend to also pay attention to whether it is possible to improve work safety, for example with an employee’s clothing giving an alert for an approaching machine, or the machine recognising a person too close to its working range.”

InToPort is a project being initiated by Steveco and South-Eastern Finland University of Applied Sciences XAMK. It will create a research and development platform for studying and developing a low-carbon transport chain from mill to port and other related issues. The focus will be on the most demanding operating environment in the chain, the port. Project participants also include an equipment manufacturer, the port company, an energy company and the local development company.

About Author